NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY

Saturday, October 22, 2005

THE REAL POCAHANTAS

THE REAL POCAHANTAS

THE POCAHANTAS/ JOHN ROLFE WEDDING

The Pocahontas Myth

In 1995, Roy Disney decided to release an animated movie about a Powhatan woman known as "Pocahontas". In answer to a complaint by the Powhatan Nation, he claims the film is "responsible, accurate, and respectful." We of the Powhatan Nation disagree. The film distorts history beyond recognition. Our offers to assist Disney with cultural and historical accuracy were rejected. Our efforts urging him to reconsider his misguided mission were spurred. "Pocahontas" was a nickname, meaning "the naughty one" or "spoiled child". Her real name was Matoaka. The legend is that she saved a heroic John Smith from being clubbed to death by her father in 1607 - she would have been about 10 or 11 at the time. The truth is that Smith's fellow colonists described him as an abrasive, ambitious, self-promoting mercenary soldier. Of all of Powhatan's children, only "Pocahontas" is known, primarily because she became the hero of Euro-Americans as the "good Indian", one who saved the life of a white man. Not only is the "good Indian/bad Indian theme" inevitably given new life by Disney, but the history, as recorded by the English themselves, is badly falsified in the name of "entertainment". The truth of the matter is that the first time John Smith told the story about this rescue was 17 years after it happened, and it was but one of three reported by the pretentious Smith that he was saved from death by a prominent woman. Yet in an account Smith wrote after his winter stay with Powhatan's people, he never mentioned such an incident. In fact, the starving adventurer reported he had been kept comfortable and treated in a friendly fashion as an honored guest of Powhatan and Powhatan's brothers. Most scholars think the "Pocahontas incident" would have been highly unlikely, especially since it was part of a longer account used as justification to wage war on Powhatan's Nation. Euro-Americans must ask themselves why it has been so important to elevate Smith's fibbing to status as a national myth worthy of being recycled again by Disney. Disney even improves upon it by changing Pocahontas from a little girl into a young woman. The true Pocahontas story has a sad ending. In 1612, at the age of 17, Pocahontas was treacherously taken prisoner by the English while she was on a social visit, and was held hostage at Jamestown for over a year. During her captivity, a 28-year-old widower named John Rolfe took a "special interest" in the attractive young prisoner. As a condition of her release, she agreed to marry Rolfe, who the world can thank for commercializing tobacco. Thus, in April 1614, Matoaka, also known as "Pocahontas", daughter of Chief Powhatan, became "Rebecca Rolfe". Shortly after, they had a son, whom they named Thomas Rolfe. The descendants of Pocahontas and John Rolfe were known as the "Red Rolfes." Two years later on the spring of 1616, Rolfe took her to England where the Virginia Company of London used her in their propaganda campaign to support the colony. She was wined and dined and taken to theaters. It was recorded that on one occasion when she encountered John Smith (who was also in London at the time), she was so furious with him that she turned her back to him, hid her face, and went off by herself for several hours. Later, in a second encounter, she called him a liar and showed him the door. Rolfe, his young wife, and their son set off for Virginia in March of 1617, but "Rebecca" had to be taken off the ship at Gravesend. She died there on March 21, 1617, at the age of 21. She was buried at Gravesend, but the grave was destroyed in a reconstruction of the church. It was only after her death and her fame in London society that Smith found it convenient to invent the yarn that she had rescued him. History tells the rest. Chief Powhatan died the following spring of 1618. The people of Smith and Rolfe turned upon the people who had shared their resources with them and had shown them friendship. During Pocahontas' generation, Powhatan's people were decimated and dispersed and their lands were taken over. A clear pattern had been set which would soon spread across the American continent. Chief Roy Crazy Horse

It is unfortunate that this sad story,which Euro-Americans should find embarrassing,Disney makes "entertainment" and perpetuates a dishonest and self-serving myth at the expense of the Powhatan Nation.

Friday, October 14, 2005

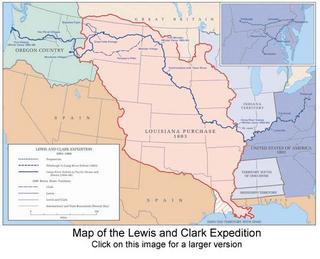

Lewis and Clark

Travel the time linechronologically or jumpdirectly to a year below.

January 18, 1803U.S. President Thomas Jefferson sends a secret message to Congress asking for approval and funding of an expedition to explore the Western part of the continent.

Spring 1803Meriwether Lewis begins his training as the expedition's leader in Philadelphia.

July 4, 1803News of the Louisiana Purchase is announced; Lewis will now be exploring land largely owned by the United States.

Summer 1803In Pittsburgh, Lewis oversees construction of a keelboat, then picks up William Clark and other recruits as he travels down the Ohio River.

Fall/Winter 1803Lewis and Clark establish Camp Wood, the winter camp for their Corps of Discovery, on the Wood River in Illinois.

March 10, 1804Lewis and Clark travel to St. Louis to attend ceremonies formally transferring the Louisiana Territory to the United States.

May 14, 1804The Corps of Discovery leaves Camp Wood and begins its journey up the Missouri River "under a gentle breeze."

July 4, 1804The Corps holds the first Independence Day celebration west of the Mississippi River.

August 3, 1804North of present-day Omaha, Nebraska, the Corps holds a council with the Oto and Missouri Indians.

August 20, 1804Sergeant Charles Floyd dies of natural causes near present-day Sioux City, Iowa; he will be the only fatality among the Corps of Discovery during the expedition.

August 30, 1804The Corps holds a council with the Yankton Sioux at present-day Yankton, South Dakota.

Early September 1804The Corps enters the Great Plains and sees animals unknown in the eastern United States.

September 25, 1804The Corps has a tense encounter with the Teton Sioux near today's Pierre, South Dakota; one of the Sioux chiefs waves his men off and conflict is averted.

October 24, 1804Near today's Bismarck, North Dakota, the Corps arrives at the villages of the Mandan and Hidatsa, buffalo-hunting tribes that live along the Missouri River.

November 4, 1804Lewis and Clark hire French-Canadian fur-trader Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife, Sacagawea, to act as interpreters on the journey ahead.

December 17, 1804The men record the temperature at 45 degrees below zero, "colder than [they] ever knew it to be in the States."

December 24, 1804The men finish building Fort Mandan, their winter quarters in present-day North Dakota.

January 1805The Corps attends a Mandan buffalo dance, performed to call buffalo to the area.

February 11, 1805Sacagawea's son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau—nicknamed Pompy by Clark—is born with assistance from Lewis.

April 7, 1805Lewis and Clark send a shipment of artifacts and specimens to President Jefferson; the "Permanent Party" heads west.

April 29, 1805The Corps marvels at the abundance of game; they kill their first grizzly bear near the Yellowstone River in Montana.

May 16, 1805One of their boats nearly overturns and Lewis credits Sacagawea with saving their most important possessions.

May 31, 1805The Corps reaches the White Cliffs region of the Missouri River.

June 1, 1805The Corps reaches an unknown fork in the Missouri and must determine which branch to choose.

June 13, 1805Lewis reaches the Great Falls of the Missouri—five massive cascades around which the men must carry all of their gear, including the canoes.

Late July 1805The expedition reaches the Three Forks of the Missouri which they name the Jefferson, Gallatin, and Madison in honor of the President, Secretary of the Treasury, and Secretary of State.

August 8, 1805Sacagawea recognizes Beaverhead Rock and knows they are close to Shoshone lands.

August 12, 1805Jefferson receives the shipment from Fort Mandan; Lewis finds the headwaters of the Missouri River, then crosses the Continental Divide and Lemhi Pass to discover that there is no Northwest Passage.

August 17, 1805The main party arrives at the Shoshone camp, where Sacagawea recognizes the chief as her long-lost brother, Cameahwait.

August 18, 1805Lewis' celebrates his 31st birthday and vows "in future, to live for mankind as I have heretofore lived only for myself."

August 31, 1805The expedition sets out for the Bitterroot Mountains with many horses and a mule acquired from the Shoshone.

September 9, 1805The men camp near today's Missoula, Montana at a spot they name Traveler's Rest while they prepare for the mountain crossing to come.

September 11, 1805The Corps begins the steep ascent into the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Mountains; the crossing will cover more than 160 miles (260 kilometers).

September 23, 1805Starving, the men emerge from the mountains near present-day Weippe, Idaho, at the villages of the Nez Perce Indians.

October 7, 1805After learning a new method to make dugout canoes from the Nez Perce, the men push off down the Clearwater River near Orofino, Idaho; it is the first time they've traveled with the current at their back in almost two years.

October 16, 1805The expedition reaches the Columbia River, the last waterway to the Pacific Ocean.

Late October 1805The Corps must run their canoes through treacherous rapids at The Dalles and Celilo Falls.

November 7, 1805Believing he sees the Pacific, Clark writes, "Ocian in View! O the joy." In reality, they are seeing only the widening estuary of the Columbia River.

November 24, 1805Having reached the Pacific, the entire expedition—including Sacagawea and Clark's slave, York—take a vote on where to build their winter quarters. They chose the Clatsop Indian side of the Columbia, and the encampment came to be called Fort Clatsop.

March 23, 1806After a winter of only 12 days without rain, the men present their fort to the Clatsop Indians and set out for home.

September 23, 1806Having found an easier route across the country, the men reach St. Louis nearly two and a half years after their journey began and are acclaimed as national heroes

http://www.discoveringmontana.com/MHSWeb/lewisandclark/css/research/imagegallery.asp

THIS HAS SOME FANTASTIC ART WORK DEPICTING LEWIS AND CLARKS JOURNEY THROUGH MONTANA

http://www.sdhistory.org/Exhibit1/mus_lcx.htm

THIS SITE DISCUSSES LEWIS AND CLARK IN SOUTH DAKOTA

Tuesday, October 11, 2005

THE GIFT OF CORN

The Gift of Maizeadapted by Vicki Lockard from a Arikara Legend

A young Arikara man was the first to discover maize. While hunting atop a high hill he scouted a large bull buffalo standing at the confluence of two rivers. While deciding how to best approach the buffalo the young man was forced to look around him closely, and was taken with the beauty of his surroundings.

Though the banks of the river were nice and timbered, the buffalo was facing north, so the young man could not take a shot from either side. He decided he would wait until the buffalo moved nearer the timbered banks or wandered into the hills or ravines where the young man could hide in shrubs.

By sundown, the buffalo had not moved at all, so the young man returned to camp disappointed. His night was not easy. He spent it thinking about how scarce food was among the people, and how much good he could have done if he had taken the buffalo.

Just before dawn the young man got up and went back to the place he left the buffalo to see if it was still nearby, had it moved at all. As the sun rose, from his spot on the high hill, the young man saw the buffalo was still in the same spot but now it faced the east. And so it stood again, all day.

Disappointed again, the young man spent another sleepless night wondering why the buffalo would stand so steadfastly in one spot without eating, drinking or lying down to rest.

The next day was the same, except the buffalo faced south and the next day west. Now the young man was determined to know why the buffalo acted in this way. He settled in to watch, and told himself the buffalo was behaving this way for some mysterious purpose, and that he, too now, was under the same mystery. He went home to sleep and yet again spent the entire night wondering.

The next day he rose before dawn and ran to his mysterious scene. The buffalo was gone! Where it had stood there was a small bush. The young man approached with disappointment, but also curiosity and awe. The plant was nothing familiar to him, surrounded by buffalo tracks, north to east and south to west. In the center was a single buffalo track from which this strange plant grew. No buffalo tracks led away from the plant.

He ran back to camp and told the chiefs and elders of his strange experience. They all traveled to the spot and found what he told them to be true. They saw the tracks of the buffalo at the spot, but no tracks coming or going from the site of the strange plant.

Now while all these men believed this plant had been given to the people by Wakanda for their use, they were not sure what that use might be.

Thinking it might need time to ripen like other plants they knew, they posted a guard to wait and see if more information would come. Soon a spike of flowers appeared, but they knew from other plants this was a flower and not the fruit. Soon a new growth appeared. First it appeared as if it had hair at its top, soon turning from green to brown.

They determined this growth was the fruit of the plant, and approached with caution and although they wanted to know what it would provided no one dared touch it. The young man finally spoke:

"Everyone knows how my life since childhood has been useless, that my deeds among you more evil than good. So, since no one would regret should any evil befall me, I will be first to touch the plant and taste its fruit."

The young man gave thanks and prayer and grasped the plant. He told the people it was firm and ripe and inside the husk it was red. He took a few kernels, showed them to the people and then carefully replaced the husks. When the youth suffered no ill effects, the people were then convinced the plant was given to them as food so they would never be hungry.

The kernels were dispersed among the people and a great, fruitful harvest was gathered in the fall. The Arikaras decided to hold a feast and they invited many tribes and six came. The Arikaras shared the kernels with their guests, and so the knowledge of maize was spread among all.

WIND CAVE ORIGIN STORY

Wasun Wiconiya Wakan

Sacred Breath or Breath of Power Cave

(Wind Cave)

Lakota oral tradition tells us that the Lakota beginning on the surface of Unci Maka (Grandmother earth) began when Wasun Wiconiya Wakan provided the opening from which the Lakota emerged from their subterranean world to the surface of the world.

After the time of creation, the world was divided into regions; the sky, the earth and waters and the underworld. When Mahpiyato created humans, they were placed in the subterranean region. At this time the Lakota called themselves the Pte Oyate, Buffalo Nation. In Lakota philosophy Pte Oyate is a metaphor meaning born of woman, physically and spiritually.

Their chief in the underworld was Wazi and his wife was Wakanka. In time Wazi and Wakanka are dissatisfied with their positions. They became selfish and sought power through their beautiful daughter, Ite (Face) . Because of their selfishness and the wrong - doings they are banished to the edge of the world with their daughter Ite. Ite was punished because she neglected her family and ignored the Pte Oyate values. One side of Ite's face is made horribly ugly. From then on she is known as Anukite which means double face or two face.

The emergence story begins with Iktomi, the spirit trickster. Iktomi transforms himself into a wolf, goes to the entrance of Wasun Wiconiya Wakan (Wind Cave) that leads to the subterranean world and tricks the humans to come to the surface of the earth by offering them food and clothing.

The first human to follow the wolf is Tokahe - The First. Despite the warning not to follow the wolf, three other men follow Tokahe and the wolf to the surface. There Iktomi still disguised as the wolf and Anukite (double face woman), daughter of Wazi and Wakanka tell the visitors that buffalo meat would keep them young forever. Tokahe and the three men return to the underworld and tell others of the wondrous things they had seen on earth.

Tokahe takes his family and persuades six men and their families to leave their subterranean home and come to the surface of the earth. Once on earth they want to return to their home when they grow tired, cold and hungry. After searching for some time they could not find the entrance to their home because Iktomi had disguised and reduced the size of the entrance .

Wazi and Wakanka find them and teach them how to make clothing, tipi homes, how to hunt buffalo and prepare food so they could live on earth. From then on the Lakota lived on the earth. The first seven families who came onto the earth with Tokahe were the original ancestors of the Seven Council Fires and they represent each star in the Big Dipper.

petroglyphs

Petroglyphs are also called carved rock, Indian writing, picture writing and rock graphics.

FREMONT UTAH

ANASAZI ARIZONIA

ANASAZI ARIZONIA

DESERT CULTURE CALIFORNIA

Petroglyphs are carved, pecked, chipped or abraded into stone. The outer patina covered surface of the parent stone is removed to expose the usually lighter colored stone underneath. Some stone is better suited to petroglyph making than others. Stone that is very hard or contains a lot of quartz does not work well for petroglyph making; however, a nice desert varnished basalt usually works very well. Pictographs are painted onto stone and are much more fragile than petroglyphs. The paint is a mineral or vegetal substance combined with some sort of binder like fat residue or blood. If the paint was not properly mixed with a binder it would not adhere well to the stone and the pictograph would quickly flake away. Pictographs were painted in locations where they would be protected from the elements: in caves, alcoves, under ledges and overhangs.

Intaglios are large ground drawings created by removing the pebbles that make up desert pavement. Intaglios are usually in the outline of animals (zoomorphs) or human-like figures (anthropomorphs). Intaglios are found on mesas along the Colorado River more so than in other places.

Monday, October 10, 2005

READING LISTS

1.

Reading List American Indian History

First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian HistoryColin G. Calloway

In the Hands of the Great Spirit: The 20,000-Year History of American IndiansJake Page

American Indian Education: A HistoryJon Allan Allan Reyhner, Jeanne Oyawin Eder

Rethinking American Indian History Donald Lee Lee Fixico

In the Spirit of Crazy HorsePeter Matthiessen

Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native AmericaJames Wilson

American Indian History: Five Centuries of Conflict and CoexistenceRobert W. Venables

Stone Heart: A Novel of SacajaweaDiane Glancy

First Strawberries: A Cherokee StoryRetold by Joseph Bruchac, Anna Vojtech

Trail of TearsJoseph Bruchac, Diana Magnuson (Illustrator)

Dog People: Native Dog StoriesJoseph Bruchac, Murv Jacob (Illustrator

Our Stories Remember: American Indian History, Culture, and Values through StorytellingJoseph Bruchac

PocahontasJoseph Bruchac

Pushing up the Sky: Seven Native American Plays for ChildrenJoseph Bruchac, Teresa Flavin (Illustrator)

History of the American Indians, 1775James Adair, Braund Kathryn E. Holland (Editor

The Last of the Mohicans (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)James Fenimore Cooper, Stephen Railton (Introduction)

The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota HistoryJoseph M. Marshall

Soul of the IndianCharles Alexander Eastman

The Lakota Way: Stories and Lessons for Living: Native American Wisdom on Ethics and CharacterJoseph M. Marshall

Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee NationJohn Ehle

Our Hearts Fell to the Ground: Plains Indian Views of how the West Was LostColin G. Calloway (Editor)

2.

Native American Reading List

Compiled by Lil Manthei

March 05

Native American Author

Grade Level

Native American Theme

Grade Level

Ceremony Leslie Marmon Silko

11-12

Jemmy Jon Hassler

7-12

Legends of the Mighty Sioux

All grades

The Owl Song Janet Campbell Hale

7-12

Indian Why Stories

All grades

The Education of Little Tree Forrest Carter

7-12

Beet Queen Louise Erdrich

11-12

Walk two Moons Sharon Creech

6-9

The Way to Rainy Mountain N.Scott Momady

9-12

The Contract Surgeon Dan O Brien

9-12

Aunt Mary Tell me a Story Mary Regina Ulmer

All grades

When the Tree Flowered John Neihardt

10-12

Winter in the Blood

James Welch

10-12

Buffalo for the Broken Heart Dan O Brien

9-12

Broken Cord Micheal Dorris

9-12

When Legends Die HaL Borland

10-12

Canyons Gary Paulson

7-9

The Night the White Deer Died Gary Paulson

7-9

Native American Non Fiction Resources

1. .The American Indians - People of the Lakes. Time Life Books.

2. Native Time - A Historical Timeline by Native Americans / by Lee Francis. - New York : St. Martins Griffin

3. Atlas of Indians of North America / by Gilbert Legay. - Barrons

4. The Apache Indians; raiders of the southwest / by Gordon Cortis, 1908- Baldwin. - New York : Four Winds Press.

5. The American Heritage Book of Indians / by William. Brandon, Alvin M., 1915- Josephyed, American Heritage.. - New York : American Heritage Pub. Co.

6. Sitting Bull and Other Legendary Native American Chiefs / by Bree.Burns. - Crescent Books.

7. Indians / by Benjamin, 1922 Capps-, Time-Life Books.. - Time-Life.

8. Scholastic Encyclopedia of the North American Indian / by James.Ciment. - New York : Scholastic Reference.

9. The Encyclopedia of Native America / by Trudy. Griffin-Pierce. - NewYork : Viking.

10. Buffalo / by Francis. Haines. - New York, Crowell

11. Geronimo; Apache freedom fighter / by Spring. Hermann. - Enslow Publishers.

12. Great Lakes Indians; a pictorial guide / by William J. Kubiak. - Grand Rapids, Mich., Baker Book House.

13. Indians on Horseback / by Alice Lee, 1910- Marriott. - New York, T.Y. Crowell Co.

14. America's Fascinating Indian Heritage / Reader's Digest., James A., ed. Maxwell. - Reader's Digest Association.

15. Through Indian Eyes; the untold story of Native American peoples /Reader's Digest.. - Pleasantville, New York : Reader's Digest

16. Sitting Bull; Sioux leader / by Elizabeth. Schleichert. - Enslow Publishers.

17. Traditional Crafts from Native North America / by Florence. Temko, Randall, illu Goochs.. - Minneapolis : Lerner Publications.

18. The Navajos; the past and present of a great people / by John Upton, 1900- Terrell. - New York, Weybright and Talley.

19. Great Chiefs / Time-Life Books., Benjamin, 1922 Capps-. - Time-Life.

20. Indians of North America / by Geoffrey. Turner. - Poole [Eng.] : Blandford Press.

21. Indians of the Arctic and Subarctic / by Paula. Younkin. - New York: Facts on File.

22. Atlas of the North American Indian / by Carl. Waldman. - New York: Facts on File.

23. Indian Chiefs / by Russell. Freedman. - New York : Holiday House.

24. The Life and Death of Crazy Horse / by Russell. Freedman, Amos, 1869-1913, il Bad Heart Bulllus.. - Holiday House.

25. American Indian Warrior Chiefs; Tecumseh, Crazy Horse, Chief Joseph, Geronimo / by Jason. Hook, Richard, ill Hook.. - Poole, Dorset : Firebird Books ; New York, N.Y. : Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub.

26. The McKenney-Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians / by James David, 1914 Horan-, Thomas Loraine, 1785-18 McKenney59. History of th. - New York, Crown Publishers.

27. American Indian Children of the Past / by Victoria. Sherrow. - Brookfield, Connecticut : The Millbrook Press.

28. Native Indian Wild Game, Fish & Wild Foods Cookbook; recipes from North American Native cooks / by David. Hunt. - New Jersey : Castle Books.

29. Early Native American Recipes and Remedies / by Duane R. Lund. - Cambridge, MN. : Adventure Publications.

30. Indian Signals and Sign Language / by George. Fronval, Daniel. DuBois. - New York : Bonanza Books.

31. Indian Clothing of the Great Lakes: 1740-1840 / by Sheryl. Hartman, Greg, illus Hudson., Joe, il Leelus.. - Liberty, UT : Eagle's View Publishing Co.

32. Encyclopedia of American Indian costume / by Josephine. Paterek. - New York : Norton,.

33. American Indian Needlepoint Workbook / by Margaret. Boyles. - New York : Collier Books.

34. Indian Handcrafts / by C. Keith. Wilbur. - Old Saybrook, Connecticut : The Globe Pequot Press.

35. Native Americans: the Indigenous People of North America / by Colin F. Taylor. - London: Salamander Books.

36. Indian Dances of North America; their importance to Indian life / by Reginald. Laubin, Gladys. Laubin. - University of Oklahome Press.

37. Turtle Island Alphabet; a lexicon of Native American symbols and culture / by Gerald. Hausman. - New York : St. Martin's Press.

38. From Abenaki to Zuni; a dictionary of Native American tribes / by Evelyn. Wolfson, William Sauts, 193 Bock9- illus.. - New York, N.Y. : Walker.

39. Encyclopedia of Michigan Indians. - St. Clair Shores, Michigan: Somerset Pub.

40. Encyclopedia of North American Indians / by Frederick E., 1947 Hoxie-. - Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

41. The Native Tribes of North America; a concise encyclopedia / by Michael G. Johnson. - New York : Macmillan Publishing Co.

42. The Magic of Spider Woman / by Lois, 1934- Duncan, Shonto, illu Begays.. - Scholastic.

43. Indian Games and Crafts / by Robert. Hofsinde. - New York, Morrow. 126 p. illus 22 cm.

44. Cherokee Removal, 1838; an entire Indian nation is forced out of its homeland / by Glen. Fleischmann. - New York, Watts.

45. Indians of the Plateau and Great Basin / by Victoria. Sherrow. - New York: Facts on File.

46. Indians of the Plains / by Elaine. Andrews. - New York: Facts on File.

47. Black Elk Speaks; being the life of a holy man of the Oglala Sioux / Black Elk, John Gneisenau, 1881-19 Neihardt73.

48. American Heritage History of the West / by David. Lavender. - New York: Bonanza Books.

49. Indians on Horseback / by Alice Lee, 1910- Marriott. - New York, T.Y. Crowell Co.

50. Plains Warrior; Chief Quanah Parker and the Comanches / by Albert. Marrin. - New York : Atheneum.

51. Life Among the Great Plains Indians / by Earle. Rice. - San Diego, CA: Lucent Books.

52. Buffalo Hunt / by Russell. Freedman. - New York : Holiday House. Buffalo Hunters. - Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books.

53. History of the Indians of the United States / by Angie, 189 Debo0-. - Norman, University of Oklahoma Press.

54. A Pictorial History of the American Indian / by Oliver, 1901- La Farge. - New York, Crown Publishers.

55. First Americans. - Alexandria, VA: Time Life Books.

56. 500 Nations; an illustrated history of North American Indians / by Alvin M., 1915- Josephyed.. - New York : Alfred A. Knopf.

57. American Indian Almanac / by John Upton, 1900- Terrell. - New York, World Pub. Co.

58. Complete How-To Book of Indiancraft / by W Ben, 188 Hunt8-1970.. - New York: Macmillan.

59. Mighty Chieftains. - Alexandria, VA: Time Life Books. 184p. 28cm.

60. American Indian Prose and Poetry; an anthology / by Margot Luise Therese (Kr"ger) 1908- ed. Astrov. - New York, John Day Co.

61. Indian Tales of North America; an anthology for the adult reader / by Tristram Potter, 1922- Coffin comp.. - Austin : University of Texas Press.

62. People of the Short Blue Corn; tales and legends of the Hopi Indians / by Harold, 1908- Courlander. - New York, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

63. The Girl Who Married a Ghost, and other tales from the North American Indian / by Edward S., 1868- Curtis1952.. - New York : Four Winds Press.

64. The Sound of Flutes and Other Indian Legends / by Richard. Erdoes, Paul. Goble. - New York : Pantheon Books.

65. Once Upon a Totem / by Christie. Harris. - New York, Atheneum.

66. Turtle Island Alphabet; a lexicon of Native American symbols and culture / by Gerald. Hausman. - New York : St. Martin's Press.

67. Myths and Legends of the Mackinacs and the Lake Region / by Grace Franks. Kane. - Black Letter Press.

68. American Indian Mythology / by Alice Lee, 1910- Marriott, Carol K., joint Rachlinauthor.. - New York, Crowell.

69. Native American Myths and Legends / by Colin F. Taylor. - Salamander Books, Limited.

70. Legend of Sleeping Bear / by Kathy-jo. Wargin. - Chelsea, MI: Sleeping Bear Press.

71. Michigan Indians; a way of life changes / by Donald. Chaput. - Hillsdale, Mich., Hillsdale Educational Publishers.

72. Legend of Mackinac Island / by Kathy-jo. Wargin. - Chelsea MI: Sleeping Bear Press.

73. Native American Myths and Legends / by Colin F. Taylor. - Salamander Books, Limited.

74. Indians of the Pacific Northwest / by Karen. Liptak. - New York: Facts on File.

75. Chippewa Child Life and Its Cultural Background / by M. Inez. Hilger. - St. Paul : Minnesota Historical Press.

76. American Indian Prose and Poetry; an anthology / by Margot Luise Therese (Kr"ger) 1908- ed. Astrov. - New York, John Day Co.

77. Song of Hiawatha / by Henry Wadsworth, 1807-1882 Longfellow.. - New York : Houghton.

78. Earth Always Endures; Native American poems / by Neil, com Philp.. - New York : Viking.

79. The McKenney-Hall Portrait Gallery of American Indians / by James David, 1914 Horan-, Thomas Loraine, 1785-18 McKenney59. History of th. - New York, Crown Publishers.

80. North American Indian Mythology / by C. A. (Cottie Arthur), 1905- Burland. - New York : P. Bedrick Books.

81. Indians of the Southeast / by Richard E. Mancini. - New York: Facts on File.

82. The Trail of Tears / by David K. Fremon. - New York : New Discovery Books.

83. Indians of the Southwest / by Karen. Liptak. - New York: Facts on File.

84. The Pueblo / by Charlotte. Yue, David. Yue. - Boston : Houghton Mifflin.

85. American Indian Warrior Chiefs; Tecumseh, Crazy Horse, Chief Joseph, Geronimo / by Jason. Hook, Richard, ill Hook.. - Poole, Dorset :

86. Firebird Books ; New York, N.Y. : Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub.

87. Way of the Warrior. - Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books.

88. War for the Plains. - Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books.

89. American Heritage History of the West / by David. Lavender. - New York: Bonanza Books.

90. Cowboys, Indians, and Gunfighters; the story of the cattle kingdom / by Albert. Marrin. - Atheneum.

91. Artists of the Old West / by John Canfield. Ewers. - Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday.

92. American Indian Women; telling their lives / by Gretchen M. Bataille, Kathleen Mullen. Sands. - Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press.

93. Indians of the Americas / by Edwin R. Embree. - Houghton Mifflin Co.

3.

Native American Authors:

[Paula Gunn Allen][Jeannette Armstrong][Shonto Begay][Kimberly Blaeser][Zitkala-Sa (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin)][Beth E. Brant (Degonwadonti)][Ignatia Broker][Joseph Bruchac][Chief Seattle][Chrystos][Ella Deloria]

[Michael Dorris][Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve][Jimmie Durham][Debra Earling][Louise Erdrich][Diane Glancy][Janet Campbell Hale][Joy Harjo][Jamake Highwater][Leanne Howe][Beverly Hungry Wolf][Emily Pauline Johnson][Maude Kegg][Winona Laduke]

[John (Fire) Lame Deer][D'Arcy McNickle][N. Scott Momaday][Mourning Dove (Christine Quintasket)][Simon Ortiz][Simon Pokagon][Carter Revard][Wendy Rose][Joe Sando][Sequoyah][Leslie Marmon Silko][Standing Bear (Ponca)][John Trudell][Velma Wallis][Anna Lee Walters][James Welch][Charles Phillip White (Whitedog)][Ray Young Bear]

NATIVE AMERICAN DAY

http://www.dickshovel.com/colum.html

http://www.dickshovel.com/colum.htmlWhen Taino Indians saved Christopher Columbus from certain death on the fateful morning of Oct. 12, 1492, a glorious opportunity presented itself. The cultures Europe of and the Americas could have merged and the beauty of both races could have flourished.

Unfortunately, what occurred was neither beautiful nor heroic. Just as Columbus could not, and did not, "discover" a hemisphere that was already inhabited by nearly 100 million people, his arrival cannot, and will not, be recognized as a heroic and celebratory event by indigenous peoples.

Unlike the Western tradition, which presumes some absolute concept of objective truth, and consequently, one "factual" depiction of history, the indigenous view recognizes that there exist many truths in the world and many legitimate recollections of any given historical event, depending on one's perspective and experiences.

From an indigenous vantage point, Columbus' arrival was a disaster from the beginning. Although his own diaries indicated that he was greeted by the Taino Indians with the most generous hospitality he had ever known, he immediately began the enslavement and slaughter of the Indian peoples of the Caribbean islands. As the eminent Columbus biographer Samuel Eliot Morison admits in his book, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Columbus was personally responsible for enslavement and murder of indigenous peoples. He was personally responsible for the design and operation of the encomienda system that tied Indians as slaves to the lands stolen from them by the European invaders.

As detailed in the American Heritage Magazine (October,1976), Columbus personally oversaw the genocide of the Taino Indian nation of what is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Consequently, this murderer, despite his historical notoriety, deserves no recognition or accolades as a hero; he deserves no respect as a visionary; and he is not worthy of a state or national holiday in his honor.

Defenders of Columbus and his holiday argue that indigenous peoples unfairly judge Columbus, a 15th century actor, by the moral and legal standards of the late 20th century. Such a defense implies that no moral or legal constraints applied to individuals such as Columbus, or countries, in 1492. As Roger Williams details in his book, The American Indian in Western Legal Thought, not only were there European moral and legal principles in 1492, but they largely favored the rights of indigenous peoples to be free from unjustified invasion and pillage by Europeans.

Unfortunately, the issue of Columbus and Columbus Day is not easily resolvable with a disposition of Columbus, the man. Columbus Day as a national, and international, phenomenon reflects a much larger dynamic that promotes myriad myths and historical lies that have been used through the ages to dehumanize Indians, justifying the theft of our lands, the attempted destruction of our nations, and the genocide against our people. Since the 15th Century, the myth of Columbus' discovery has been used in the development of laws and policies that reek of Orwell's doublespeak: theft equals the righteous spread of civilization, genocide is God's deliverance of the wilderness from the savages, and the destruction of Indian societies implies the superiority of European values and institutions over indigenous ones.

Columbus Day is a perpetuation of racist assumptions that the Western Hemisphere was a wasteland cluttered with savages awaiting the blessings of Western "civilization." Throughout the hemisphere, educational systems perpetuate these myths - suggesting that indigenous peoples have contributed nothing to the world, and, consequently, should be grateful for their colonization and their microwave ovens.

As Alfred Crosby, Kirkpatrick Sale, and Jack Weatherford have illustrated in their books, not only was the Western Hemisphere a virtual ecological and health paradise prior to 1492, but the Indians of the Americas have been responsible for such revolutionary global contributions as the model for U.S. constitutional government, agricultural advances that currently provide 60 percent of the world's daily diet, and hundreds of medical and medicinal techniques still in use today.

If you find it difficult to believe that Indians had developed highly complex and sophisticated societies, then you have been victimized by an educational and social system that has given you a retarded, distorted view of history. The operation of this view has also enabled every country in this hemisphere, including the U.S., to continue its destruction of Indian peoples. From the jungles of Brazil to the highlands of Guatemala, from the Chaco of Paraguay to the Supreme Court of the United States, Indian people remain in a perpetual state of danger from the systems that Christopher Columbus began in 1492.

Throughout the Americas, Indian people remain at the bottom of every socioeconomic indicator, we are under continuing physical attack, and are afforded the least access to economic, political, or legal redress. Despite these constant and unbridled assaults, we have resisted, we have survived, and we refuse to surrender any more of our homeland or to disappear into the romantic sunset.

To dignify Columbus and his legacy with parades, holidays and other celebrations is intolerable to us. As the original peoples of this land, we cannot, and will not, countenance social and political festivities that celebrate our genocide. We are embarking on a two- pronged campaign in the quincentenary year to confront the continuing racism against Indian people.

First, we are advocating that the divisive Columbus Day holiday should be replaced by a celebration that is much more inclusive and more accurately reflective of the cultural and racial richness of the Americas. Such a holiday will provide respect and acknowledgement to every group and individual of the importance and value of their heritage, and will allow a more honest and accurate portrayal of the evolution of the hemisphere. It will also provide an opportunity for greater understanding and respect as our societies move ahead into the next 500 years. Opponents to this suggestion react as though this proposal is an attack on ancient time-honored holiday, but Columbus Day has been a national holiday only since 1971 - and in 1991, hopefully, we can correct the errors of the past, moving forward in an atmosphere of mutual respect and inclusiveness.

Second, and related to the first, is the advancement of an active militant campaign to demand that federal, state, and local authorities begin the removal of anti-Indian icons throughout the country. Beginning with Columbus, we are insisting on the removal of statues, street names, public parks, and any other public object that seeks to celebrate or honor devastators of Indian peoples. We will take an active role of opposition to public displays, parades, and celebrations that champion Indian haters. We encourage others, in every community in the land, to educate themselves and to take responsibility for the removal of anti-Indian vestiges among them.

For people of goodwill, there is no better time for the re-examination of the past, and a rectification of the historical record for future generations, than the 500th anniversary of Columbus' arrival. There is no better place for this re-examination to begin than in Colorado, the birthplace of the Columbus Day holiday.

Russell Means and Glenn Morris wrote this position statementin 1991 on behalf of the American Indian Movement of Colorado,1574 South Pennsylvania St., Denver, CO

INTRODUCTION

Narrative:

Imaciyapi Lil Manthei. I am from the Cheyenne River Reservation in western South Dakota. I grew up on a ranch about 20 miles north of Thunder Butte. My father is Paul Manthei, and my mother is Norina Grate Manthei. I am the oldest of five children. I was not raised in a traditional way, but as I grew older I sought to learn Lakota culture. My mother’s grandfather is from the Cherokee Nation, so my blood is Cherokee, but my cante is Lakota. I have always lived on the reservation; except for when I attended college. Harold and Geraldine Condon, Valerie and Stephanie Charging Eagle, and Keeler and Frieda Condon have been my guides and mentors teaching me the Lakota way. Generosity, fortitude, courage, and spirituality are the values that guide my life. I have eight grandchildren, six adopted children, and one son.

My educational experience began in a one-room school house in Ziebach County. My first eight years of education where completed in this one-room schoolhouse. At the beginning of my freshman year in high school, my family moved to the Black Hills. This proved to be a difficult move for me. I had a hard time adjusting to my new environment. At sixteen, I was married and had my son. The need for an education, though, remained a goal in my life, and I completed my GED in 1975. My son was then two-years old.

In 1984, I began my college career at Black Hills State College (Before it became a university). I attended for three semesters and then because of family issues, I returned home. The desire, though, for an education did not disappear. In 1989, I returned to college at Dakota State University in Madison, South Dakota. While at DSU, I was involved in Rodeo Club, and I was an organizer for a Non-traditional Students Organization and also for a Native American Club. I also worked on the college paper as a reporter and advertising representative. I attended two years at DSU, and then transferred to South Dakota State University in 1991. I transferred to SDSU, because I wanted a minor in Indian Studies, and DSU did not offer classes in Native American culture. I attended SDSU until 1993, and then my desire to return to western South Dakota led me to transfer to Black Hills State University. I returned to were I had started. I graduated from Black Hills State University in December of 1995. I was the first generation in my family to receive a four year college degree. I graduated with a Bachelors of Science degree in Secondary Education. My major was English and my minor was American Indian Studies.

My teaching career began at Takini School on the Cheyenne River Reservation. I did my student teaching at Takini in the fall of 1995. Wendy Mendoza and Dana Brave Eagle were my cooperating teachers for my student teaching experience. I completed my student teaching in December of that year, and then was given a contract from Takini School. While at Takini, I taught 9 and 10 Composition, World Literature, American Literature, Research Writing, Speech, and Native American Literature. I was also advisor for the daily bulletin and the newsletter, advisor for the senior class and Student Council. I assisted with Rodeo Club and Native American Club.

In 1997, I accepted a position at Crow Creek Tribal Schools. While at Crow Creek, I taught Freshman Composition and Literature, World Literature, Speech, Native American Literature, Creative Writing, and Reading Skills. I was advisor for the sophomore class, and The Drumbeat (the school paper). I also assisted with Native American Club. I also was Oral Interpretation coach.

I was at Crow Creek for five years, when again my desire to return West River became overwhelming. It was time to go back home. In the spring of 2002, I applied for a position at Little Wound School and was offered a contract. I accepted. I began at Little Wound in the fall of 2002. I taught English Nine. I also accepted a position as Adjunct professor at Oglala Lakota College. I taught 083 Developmental Reading and Writing and 093 Basic Reading and Writing. In January of 2003, I applied for the Graduate Program at Oglala Lakota College and took classes towards a Lakota Leadership and Management Degree with Education Emphasis. . I applied and was accepted to the consortium for the Masters Degree in Curriculum and Instruction. I completed the program in July 2005 with Master of Arts. I currently am Elementary computers/technology consultant at Wagner Community School , and adjunct professor at Kilian Community College . I teach Native American History and Culture.